Kaji is sent to the Japanese army labeled Red and is mistreated by the vets. Along his assignment, Kaji witnesses cruelties in the army and revolts against the abusive treatment […]

Kaji is sent to the Japanese army labeled Red and is mistreated by the vets. Along his assignment, Kaji witnesses cruelties in the army and revolts against the abusive treatment […]

After handing in a report on the treatment of Chinese colonial labor, Kaji is offered the post of labor chief at a large mining operation in Manchuria, which also grants […]

After the Japanese defeat to the Russians, Kaji leads the last remaining men through Manchuria. Intent on returning to his dear wife and his old life, Kaji faces great odds […]

The mother of a feudal lord’s only heir is kidnapped away from her husband by the lord. The husband and his samurai father must decide whether to accept the unjust […]

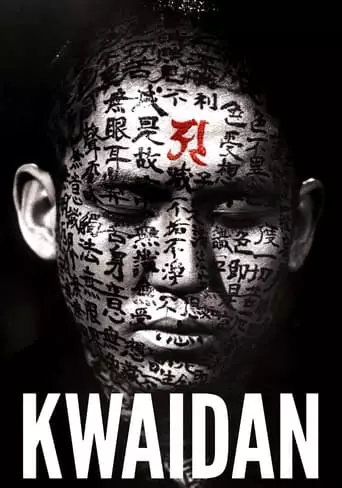

Taking its title from an archaic Japanese word meaning ghost story, this anthology adapts four folk tales. A penniless samurai marries for money with tragic results. A man stranded in […]

Down-on-his-luck veteran Tsugumo Hanshirō enters the courtyard of the prosperous House of Iyi. Unemployed, and with no family, he hopes to find a place to commit seppuku—and a worthy second […]

Masaki Kobayashi: The Humanist Filmmaker of Japanese Cinema

Masaki Kobayashi (1916–1996) is one of Japan’s most revered filmmakers, celebrated for his profound and unflinching exploration of morality, justice, and the human condition. Over a career spanning several decades, Kobayashi crafted films that challenged societal norms, critiqued authority, and examined the struggles of individuals against oppressive systems.

Known for masterpieces such as The Human Condition trilogy (1959–1961), Harakiri (1962), and Kwaidan (1964), Kobayashi’s films are marked by their meticulous composition, emotional depth, and moral complexity. His works remain a cornerstone of Japanese cinema, earning him international acclaim and enduring respect.

Early Life and Influences

Masaki Kobayashi was born on February 14, 1916, in Hokkaido, Japan. He studied art history at Waseda University, where he developed a deep appreciation for philosophy, literature, and the arts.

Kobayashi’s worldview was profoundly shaped by his experiences during World War II. Drafted into the Imperial Japanese Army in 1942, he served in Manchuria and later became a prisoner of war in an Allied camp. His opposition to the war and the militaristic ideology of the time left a lasting imprint on his work, leading him to become a staunch critic of authoritarianism and blind obedience.

Early Career in Film

After the war, Kobayashi joined Shochiku Studios as an assistant director. He worked under prominent filmmakers such as Keisuke Kinoshita, whose influence is evident in Kobayashi’s early films. His directorial debut came in 1952 with My Sons’ Youth, a light family drama that hinted at his ability to portray human relationships with sensitivity.

However, it was Kobayashi’s shift to socially conscious and politically charged narratives that defined his career.

The Human Condition Trilogy (1959–1961)

Kobayashi’s magnum opus, The Human Condition (Ningen no Jōken), is a nine-hour epic divided into three films:

No Greater Love (1959)

Road to Eternity (1959)

A Soldier’s Prayer (1961)

Based on Junpei Gomikawa’s novel, the trilogy follows Kaji, a pacifist and idealistic labor supervisor, as he navigates the horrors of war, labor camps, and moral compromise. Played by Tatsuya Nakadai, Kaji is a stand-in for Kobayashi himself, embodying the filmmaker’s pacifist ideals and resistance to authoritarianism.

The trilogy is a searing indictment of war and human cruelty, exploring themes of dehumanization, moral conflict, and the resilience of the human spirit. Its epic scale, unflinching realism, and emotional depth solidified Kobayashi’s reputation as a master filmmaker.

Harakiri (1962)

Following The Human Condition, Kobayashi directed Harakiri (Seppuku), a samurai drama that deconstructed the rigid codes of feudal Japan. The film tells the story of Hanshiro Tsugumo, a ronin who seeks justice after his family is destroyed by the hypocrisy of a samurai clan.

Starring Tatsuya Nakadai in one of his most powerful performances, Harakiri is a scathing critique of institutionalized honor and the exploitation of tradition for power. The film’s bold narrative structure, stunning cinematography, and moral depth earned it the Special Jury Prize at the 1963 Cannes Film Festival.

Kwaidan (1964)

Kobayashi ventured into supernatural storytelling with Kwaidan, a visually stunning anthology of four ghost stories based on Lafcadio Hearn’s collection of Japanese folktales.

Each segment of Kwaidan—The Black Hair, The Woman of the Snow, Hoichi the Earless, and In a Cup of Tea—is meticulously crafted, blending traditional Japanese aesthetics with haunting visuals. The film’s use of vibrant colors, stylized sets, and eerie soundscapes creates an otherworldly atmosphere, making it a landmark in the horror genre.

Kwaidan received international acclaim, winning the Special Jury Prize at the 1965 Cannes Film Festival and solidifying Kobayashi’s reputation as a filmmaker of unparalleled artistry.

Later Works and Legacy

Kobayashi continued to explore themes of morality and justice in his later films, including:

Samurai Rebellion (1967): A powerful critique of feudal oppression and the sacrifices made in the name of honor.

Inn of Evil (1971): A nuanced exploration of crime and redemption.

Though his output slowed in the 1970s, Kobayashi remained an influential figure in Japanese cinema. He served as a mentor to emerging filmmakers and collaborated on projects that reflected his commitment to social justice and artistic integrity.

Themes and Style

Masaki Kobayashi’s films are defined by:

Moral Conflict: His characters often grapple with ethical dilemmas, reflecting his own resistance to conformity and authority.

Critique of Power: Kobayashi’s works challenge the abuses of power, from feudal hierarchies to modern militarism.

Visual Precision: Known for his meticulous compositions and use of space, Kobayashi’s films are visually striking and deeply immersive.

Humanism: At the heart of Kobayashi’s cinema is a profound empathy for individuals and their struggles against oppressive systems.

Impact and Recognition

Masaki Kobayashi’s uncompromising vision and commitment to social justice have left an indelible mark on world cinema. His films continue to resonate with audiences for their emotional depth, moral complexity, and artistic brilliance.

Today, Kobayashi is celebrated alongside Akira Kurosawa, Yasujirō Ozu, and Kenji Mizoguchi as one of the great masters of Japanese cinema. His works serve as a timeless reminder of the power of film to confront injustice and illuminate the human condition.

Conclusion

Masaki Kobayashi’s legacy is one of courage, artistry, and unwavering commitment to truth. Through his films, he gave voice to the voiceless, challenged the status quo, and created stories that transcend time and culture.

In a world often marked by conflict and inequality, Kobayashi’s films remain a beacon of hope, urging us to question authority, seek justice, and embrace our shared humanity.