Shuhei Hirayama is a widower with a 24-year-old daughter. Gradually, he comes to realize that she should not be obliged to look after him for the rest of his life, […]

Shuhei Hirayama is a widower with a 24-year-old daughter. Gradually, he comes to realize that she should not be obliged to look after him for the rest of his life, […]

A lighthearted take on director Yasujiro Ozu’s perennial theme of the challenges of intergenerational relationships, Good Morning tells the story of two young boys who stop speaking in protest after […]

Noriko is perfectly happy living at home with her widowed father, Shukichi, and has no plans to marry — that is, until her aunt Masa convinces Shukichi that unless he […]

When a theater troupe’s master visits his old flame, he unintentionally sets off a chain of unexpected events with devastating consequences. Floating Weeds (1959), directed by Yasujirō Ozu, is a […]

A 28-year-old single woman is pressured to marry. Early Summer (1951), directed by Yasujirō Ozu, is a poignant exploration of family dynamics and societal expectations in post-war Japan. The narrative […]

The elderly Shukishi and his wife, Tomi, take the long journey from their small seaside village to visit their adult children in Tokyo. Their elder son, Koichi, a doctor, and […]

Yasujirô Ozu: The Master of Subtle Cinema

Yasujirô Ozu (1903–1963) is one of the most celebrated filmmakers in the history of cinema, renowned for his delicate and profound explorations of family, relationships, and the passage of time. With a career spanning over three decades, Ozu’s films are characterized by their understated storytelling, meticulous composition, and a deep sensitivity to the human experience.

Often referred to as the “most Japanese” of Japanese directors, Ozu’s work transcends cultural boundaries, resonating universally with audiences for its emotional authenticity and timeless themes. His masterpieces, including Tokyo Story (1953), Late Spring (1949), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962), remain cornerstones of world cinema.

Early Life and Career Beginnings

Yasujirô Ozu was born on December 12, 1903, in Tokyo, Japan. Raised in Matsuzaka, Mie Prefecture, Ozu developed a love for storytelling and cinema early in life. After studying at the Tokyo School of Commerce, he joined Shochiku Film Company in 1923 as an assistant cameraman and later as an assistant director.

Ozu made his directorial debut in 1927 with Sword of Penitence, a silent film that marked the beginning of his long association with Shochiku. His early works, often comedic or melodramatic, reflected the influence of Hollywood filmmakers like Ernst Lubitsch and Harold Lloyd.

Evolution of a Unique Style

By the 1930s, Ozu began to develop the distinctive style that would define his career. He shifted from melodramatic narratives to a more restrained and contemplative approach, focusing on the nuances of everyday life.

Key elements of Ozu’s style include:

The Tatami Shot: Ozu’s signature low-angle camera placement mimics the perspective of someone seated on a tatami mat, creating an intimate connection with the characters.

Static Camera: His use of a stationary camera emphasizes the stillness and subtlety of his compositions.

Elliptical Editing: Ozu often omitted dramatic moments, focusing instead on their aftermath, allowing audiences to fill in the emotional gaps.

Themes of Transience: Ozu’s films frequently explore the impermanence of life, the inevitability of change, and the bittersweet nature of human relationships.

Major Works and Legacy

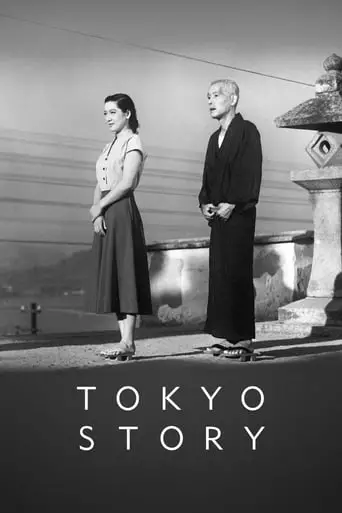

Tokyo Story (1953)

Considered Ozu’s magnum opus, Tokyo Story is a poignant exploration of generational divides and the changing dynamics of family life. The film follows an elderly couple who visit their children in Tokyo, only to find themselves neglected in the busy modern city.

With its restrained performances and understated emotional depth, Tokyo Story is a masterpiece of minimalist filmmaking. It is widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made, consistently appearing at the top of international critics’ polls.

Late Spring (1949)

Late Spring is a deeply moving portrayal of the bond between a widowed father and his devoted daughter. The film examines themes of duty, sacrifice, and the inevitable separation that accompanies life’s transitions.

Starring Setsuko Hara, often referred to as Ozu’s muse, Late Spring epitomizes the quiet emotional power of Ozu’s storytelling.

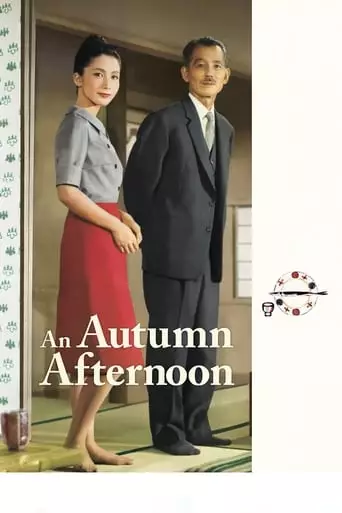

An Autumn Afternoon (1962)

Ozu’s final film, An Autumn Afternoon, revisits familiar themes of family and generational change. The story centers on an aging widower who arranges his daughter’s marriage, reflecting on his own loneliness in the process.

The film’s serene yet melancholic tone serves as a fitting conclusion to Ozu’s career, encapsulating his lifelong exploration of life’s fleeting beauty.

Recurring Themes in Ozu’s Cinema

Ozu’s films are deeply rooted in Japanese culture, yet their themes resonate universally:

Family Dynamics: His stories often focus on the tensions and connections within families, particularly between parents and children.

Generational Conflict: Ozu frequently depicted the clash between traditional values and modernity, reflecting the rapid societal changes in postwar Japan.

The Passage of Time: His films are imbued with a sense of impermanence, capturing the quiet, often unnoticed moments that define human existence.

Everyday Life: Ozu’s focus on the mundane and ordinary highlights the profound beauty and complexity of simple human interactions.

Critical Reception and Legacy

Although Ozu’s work was initially underappreciated outside Japan, his reputation grew significantly after his death in 1963. Today, he is celebrated as one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, influencing directors such as Wim Wenders, Jim Jarmusch, and Hirokazu Kore-eda.

Ozu’s films continue to captivate audiences with their universal themes and masterful craftsmanship. His ability to convey deep emotional truths through simplicity and restraint remains unparalleled in the history of cinema.

Conclusion

Yasujirô Ozu’s films are a testament to the power of subtlety and the beauty of the ordinary. Through his meticulous compositions and heartfelt narratives, he captured the essence of human relationships and the quiet struggles of life.

Ozu’s legacy endures as a beacon of cinematic artistry, reminding us that even the smallest moments can carry profound meaning. His work continues to inspire filmmakers and audiences alike, offering a timeless reflection on the fragility and resilience of the human spirit.